Monday Morning, Seven Fifteen

It’s the normality which shocks her. The fact that it’s possible.

She has watched them this past month, day after day, but there has never been a sign, not even some small indication, that their lives are anything other than happy.

This morning will be the same. A weekday, so it’s the school run, and she knows how it will play out.

At seven forty-five the car will bleep with a flash of orange lights, followed by the front door opening. Two girls, young still, will stumble out onto the driveway, while behind, their mother, laden with school bags and harried – though not dishevelled, she is never dishevelled – will fumble with the keys and shout, ‘You guys belt up in there, okay?’

The girls will giggle and slam the car doors shut with an expensive sounding thud, yelling, ‘Okay! Okay!’ frustrated already with this maternal concern. In a few years they will no doubt roll their eyes at her but not today, not yet.

‘Maybe this is how they give themselves away?’ she wonders. ‘It’s the things they don’t say and do which hint at what happened.’

Or perhaps she’s reading too much into the situation? She’s been doing that lately. Seeing things that aren’t there. Interpreting things in ways no-one else would.

Though who can blame her? She cannot shake things off so easily, she can’t erase her memories, forget the sight of him. It’s still with her. It’s still vivid.

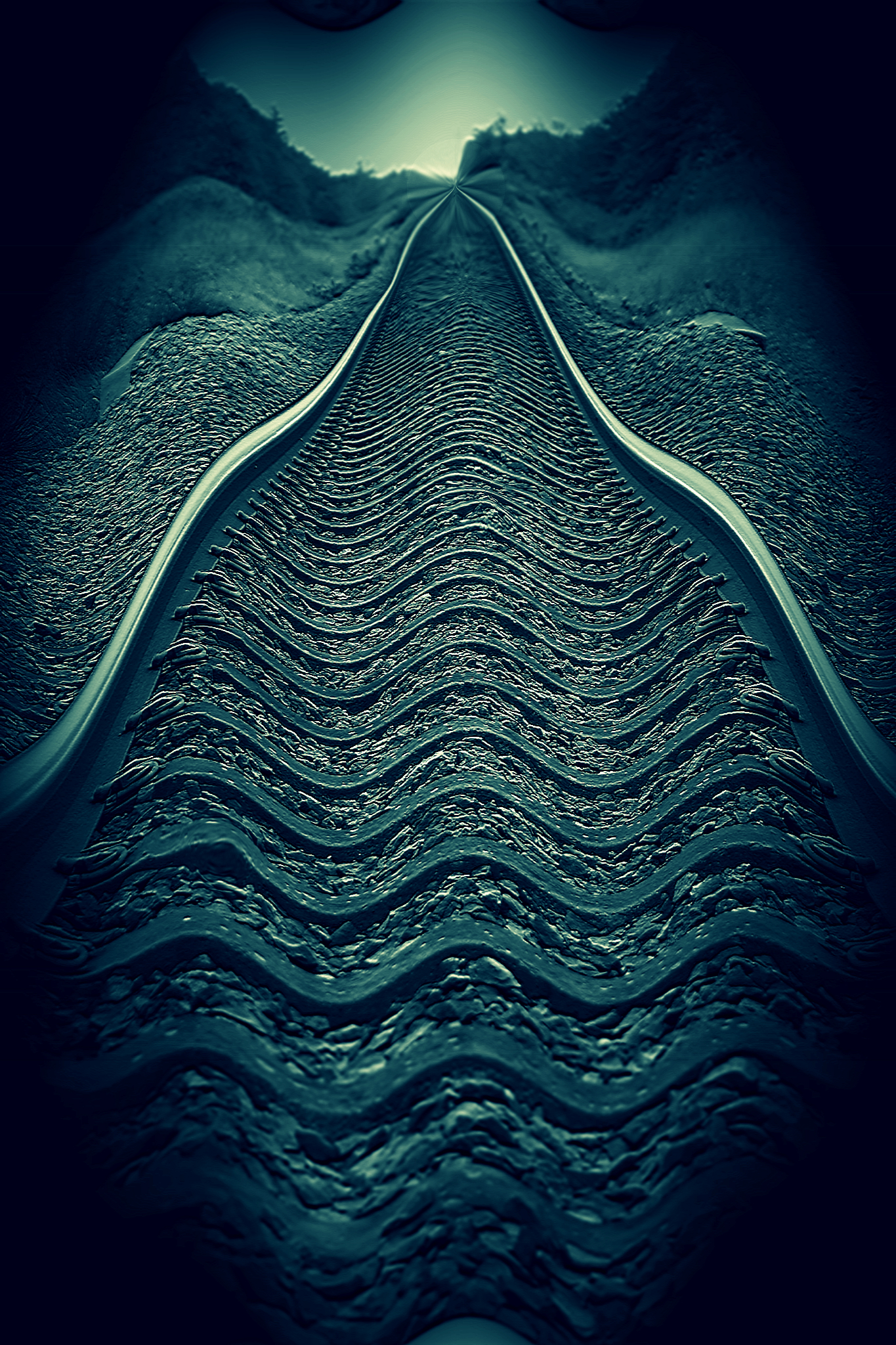

Even now, when she thinks about it, she can feel the rush of air that swept through the station that morning.

Everyone had blinked and taken a step backwards as the train powered through, and as they blinked, he jumped, the train coming to a halt a few hundred meters down the line.

Afterwards, the driver, stunned and apologetic, had explained that he hadn’t even seen him. All he’d heard was a thud, then a few seconds of confusion before it registered, before he realised he had hit something. Someone.

That was the funny thing about the whole incident. No-one on the platform could recall seeing a thing. It was only that thud, followed by the screech of breaks, which had alerted anyone to the fact that something unusual had happened, because the seven fifteen express never stops at this station.

Later, when they were questioning people on the platform, she’d heard one of the police officers comment on it, as if he couldn’t quite believe it.

‘How could something like this happen without anyone seeing it?’ he’d asked.

They’d handed out cards anyway, just in case it was the shock that was blocking it from their minds. Trauma, they explained. It can do things like that to you.

She’d thought about that, all those people on the platform, having a split second of their lives obliterated from their memories, as if they’d all died together for an instant.

The train came in. Everyone blinked. The man was gone. And a moment was erased from their lives just like that.

‘Is that what trauma is?’ she wondered. ‘Is that how she should describe herself? Traumatised?’

What she’d seen was this.

She didn’t see his face. Just his back. He was wearing a long black coat, unbuttoned, and when he stepped from the platform, it opened up, like the wings of some strange black bird.

There was something dreamlike about it. Something graceful and quiet, serene even. Like a macabre but beautiful dance.

In that instant, as he glided down from the platform into the path of the train, it hardly seemed like death at all.

Many times since she has wondered if it was just an accident, that all he’d meant to do was catch the air and glide a while alongside the train as it sped through the station. That death had never been on his mind.

Perhaps it was this which made it seem like such a quiet end. The train rushing through, sucking all the air out and leaving everything airless and still as a vacuum. That thud the only violent thing about the whole incident.

That was the thing she would have the most difficulty explaining to anyone. The peacefulness of it. And it is this, more than anything, which has stayed with her.

More than the noise he made when the train hit. More than the shrill shriek of the breaks as the train came to a halt. More than the terrible image of the sheer bloody horror that lay on the tracks below.

In the paper a few days later, there had been a small paragraph detailing the incident.

Forty-five. A wife. Two kids. Just a regular guy on his way to work. No hint of what was to come.

‘Son of a bitch.’

Her outburst confusing Jimmy, because she’s not one to curse.

‘Who, me?’

She hadn’t realised she’d said it out loud. Anger had taken control of her, because almost immediately the images came. The scene in his home that morning. The apparent ordinariness of it. Cups and plates on the breakfast table, the smell of coffee, kids laughing, the wife busy and oblivious. Happy even, with the domestic ordinariness.

And all the while, him knowing what he had planned. Putting on his coat. Saying his goodbyes. No-one thinking much about it, because it’s just another Monday morning and everyone’s in a rush.

But he would have known. He would have stood amid all that simple happiness and known of the horror that was to come.

The hope she’d had that he’d been caught by the wind, that death was far from his mind, was a delusion she realised. Nothing but a magical idea she had concocted for herself to keep the truth at bay.

‘No,’ she’d told Jimmy. ‘I mean that man, the one who jumped. There’s a piece in the paper about him.’

And Jimmy had leaned across the table and slipped the paper from her hands and read.

‘Karen, I don’t think you should read this stuff,’ he told her. ‘What good will it do to know about him? His family?’

But she wanted so badly to do just that. To know who he was, why he did what he did. There’s no explaining it, why she needs to know such things, knowing won’t change the outcome, knowing won’t illuminate anything. But the pull of it consumes her just the same and she is powerless to stop it.

She said none of this to Jimmy. Just as she has said nothing to him about what she saw that morning. She wants Jimmy to simply keep being Jimmy. To always fold up the paper and declare matters closed.

She wishes she could do the same. Just push it to one side and move on with daily life.

And she would, were it not for the strange belief which has overcome her, the idea that she was fated to witness it. That there’s a reason for it.

Because she wasn’t supposed to have been there. Mondays are her day off, but that morning she’d agreed to stand in for Eileen as a favour.

So, when he jumped, her first thought had been: ‘I wasn’t supposed to see this.’

And she was angry that the two events should collide like that. Her being there. Him jumping. But her anger had quickly subsided and turned into something else, though what it was she couldn’t say.

All she knew was that it manifested itself this way. Standing outside the family home, watching them, the three survivors. Looking for something without knowing what it is.

And if Jimmy could see her, if Jimmy knew she did this, what would she tell him? How could she explain it?

‘I just need to see it, Jimmy. See why it was he did what he did. What was it about this life that made him want to jump?’

Which is the wrong question of course, because there is nothing wrong with this life. Nothing she can see, at least. And anyway, how can you apportion blame to children as small as these? How can you apportion blame to a wife who, assaulted with a horror such as this, still understands it’s the small things which matter? Who still tells her kids to buckle up in the back?

Seven forty-five and right on schedule the door opens. Only this time something is different. No giggling girls, no harried rush.

Just the mother in the doorway looking straight at her.

And though she wants to look away, though she feels a knot of panic contract in her gut, she finds she cannot move. Her gaze remains fixed as she watches the woman click shut the door and make her way down the driveway towards her.

She hears the questions before they are uttered ‘Who are you? What do you want from us?’

‘And the answer?’ she thinks. ‘What’s the answer?’

‘Is it Tom?’ the mother asks. ‘Is that why you’re here?’

It throws her, that she calls him Tom. The informality of it. The way it hints at how they were together. Shortened names, familiar names. Happy and intimate. As if the love is still there.

In the newspaper, they had called him Thomas and she had become used to him by this name. Had attached it to the image of his black coat. A Thomas she could imagine jumping. But Tom? There was something too lively about it. Cartoonish, yes, that’s what it was, that was probably it.

‘Yes,’ she nods, ‘it’s about Tom.’

‘You knew him?’ the mother asks, and she notices the way her eyes narrow, the tiny trace of a furrow appearing between the eyes. She is wary of the reply. And this also hints at something, though if it is the thing she is looking for, the answer, the why, she can’t be sure.

‘No,’ she admits, ‘I didn’t know him.’

They sit on a bench on the front porch, ‘just in case there are things you need to tell me that the children shouldn’t hear,’ the mother explains.’There are things I need to keep outside our home.’ And something about the way she says it suggests she has had to repeat this often these past weeks.

She thinks of all the things she shouldn’t say. The black bird and the many times she has cursed his name.

‘I was there,’ is all she says, because she doesn’t know how else to begin, doesn’t know what part of this can be made to make any sense.

And the mother looks at her and doesn’t understand.

‘On the platform,’ she explains. ‘The day he jumped. I was a witness.’

‘A witness,’ the mother muses.

And perhaps it’s the choice of words which convinces her, calms her, because she nods and says, ‘I never thought of that,’ she continues, ‘that there were other people there. That there were witnesses.’

And she finds she also likes the way it sounds. Witness. As if they are talking about someone else. This witness person. Someone other. An idea like that – it’s something she can hold on to.

‘I don’t need to know what happened, if that’s what you’re here for?’ the mother whispers, as if it takes all her courage to speak. ‘There’s enough I can imagine. And details don’t help.’

But she hasn’t come here to talk about that day. What it is, is simpler than that.

‘I wanted to say I was sorry,’ she explains.

And the mother shakes her head.

‘Sorry? Why? You say that as if it’s your fault.’

‘Sometimes it feels that way.’

Though just saying this feels like a revelation. As if she is giving herself permission for something. ‘But what?’ she wonders. ‘Permission to forget? Perhaps, perhaps.’

‘I can’t help you,’ the mother explains. ‘If that’s what you’re after? I can’t help. I don’t have any answers.’ The truth of this statement right there in the hollowness in her eyes.

And she wants to tell her that this is what she also feels. Helpless. Unable to explain anything.

‘I know how that feels,’ she says. Though as she says it she knows it’s impossible. Knows this is the wrong thing to say. All she knows is what she saw that day. All she knows is what she read in the paper. Old news now crumpled and discarded as the world, inevitably, moves on.

‘I know how that feels.’ Really?

And she has said too much, pressed too far, demanded an intimacy that she has no claim upon, the idea that she can possibly share something with this mother, this wife. It’s not true and both of them accept it.

The mother shakes her head and echoes her very thoughts, as if to confirm it.

‘Do you? Do you? How can you know how it feels?’

Then she gets up from the porch seat and heads to the door.

‘You’ll figure it out,’ she says. ‘We all figure it out. Even Tom, in his own way, I suppose.’

And with that she closes the door and leaves her seated there on the front porch.

From inside the house she can hear the sound of voices, questions and pleas. ‘Who is that woman, Mummy?’ The crack in the routine reverberating round the house. Something she has caused without meaning to.

‘I’m a witness,’ she wants to tell them. ‘Just a witness.’

And again, it lifts her, saying this, attributing something to the incident which is nothing more than an unfortunate chain of events. Something which can be stated simply, matter of factly. No need for explanation, no need for understanding. She was simply there.

And that feeling which has washed over her time and again, the strange visceral urge to know how it feels to float, to glide down on to the rails. It is nothing more than this – a feeling, a sensation, the memory of something she has witnessed.

Beyond her. Not within.

In the newspaper, they had called him Thomas and she had become used to him by this name. Had attached it to the image of his black coat. A Thomas she could imagine jumping. But Tom? Click To Tweet